Healthcare Consumerism and the Move Toward Wellness

A Four-Part Series by Will Stabler

About This Series

I wrote this article series 2019 as consumerism was presumably taking hold in the healthcare industry. The series examines several potential models for a consumer-centric healthcare system.

Articles in This Series

Healthcare Consumerism and the Move Toward Wellness

By Will Stabler

First published on Jan 4, 2019

This is the first in a series of articles exploring potential models for a consumer-centric healthcare system.

The U.S. healthcare system is in the middle of a move from the old fee-for-service structure to what is being called “value-based care.” Presumably, this means we are transitioning from a reactive, acute-care/chronic-care model based on patient volume to one that is based on prevention and keeping people well.

The pundits often vilify fee-for-service and posit that the concept of value-based care is superior because it is patient-centered. Does this have to be a binary discussion—fee-for service bad, value-based good? Must it be looked at as a zero-sum argument?

I hope not. Can we find true wellness and value at the same time and get what we pay for to boot?

What Does the Future Model Look Like?

The implication is that the model we are moving toward will be highly focused on the patient as an involved player. The evidence of that evolution should be a rising wave of consumerism as the transformation takes place, and we are seeing some of that already. But the reality so far is that this move is largely being accomplished without much involvement from the consumer, making it look more like the paternalistic model that has always been a hallmark of the U.S. healthcare system.

Powerful actors from the payer communities, working within an architecture influenced and/or dictated by the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and other government regulatory bodies, are driving fundamental change in the availability and delivery of care. This seismic shift is occurring at a rapid clip, but realistically, it looks very likely that most Americans will continue to get access to health care via their employers for the foreseeable future. Real consumer disruption at the point of care does not seem to be in the cards for the near term.

The reality so far is that this move is largely being accomplished without much involvement from the consumer, making it look more like the paternalistic model that has always been the hallmark of the U.S. healthcare system

There are approximately 325 million people in the United States. Of them, 49 percent have health insurance coverage provided by an employer and another 7 percent purchase their own health insurance (Kaiser Family Foundation, 2018). What would happen for these consumers and their neighbors who have access through Medicaid (19.4 percent) and Medicare (16.7 percent) if they could shape the coverage and delivery of healthcare that is most beneficial for themselves? And what newfound responsibility for their own well-being would rightfully come attached?

How do we get to the point where consumers are crafting their healthcare services and/or their health plans? How would they do that? How would they even know where to begin? Currently, for the vast majority of the country, somebody in an HR department is working with the payers to provide benefit programs for patients/consumers, or bureaucrats in the state or federal government are doing it for them through Medicare, Medicaid or the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act (ACA). If HR departments were not partnering with insurance companies to do that, who would then “partner” with the insurance companies? Who would help the consumer assess choices and value?

Who knew healthcare could be so complicated?

Without further questioning the thesis of those advocating and effectuating this evolution to value-based care, what if we hit PAUSE and turned the thinking upside down, imagining what it would mean to have a healthcare ecosystem that is truly patient-centered and consumer-driven?

The purpose of this series of articles is to present several scenarios that might look like true consumer-driven models, and then point out both the potential advantages and the pitfalls of each without advocating for a given position until the end. Only after all variants have been considered will I venture a recommendation. It could be one of the models in its current form. It could be a hybrid of x, y and z. It could be the baby being thrown out with the bathwater. We will have to wait and see. (Presumably, a thorough analysis will make it worth the wait.)

So first, let’s set the stage.

What Does "Patient-Centered" Really Mean?

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) Committee on the Quality of Health Care in America introduced the concept of “patient-centered” in its landmark 2001 report titled, “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century.” That publication presented the conclusion that a sweeping redesign of this country’s systems of care was needed and that incremental improvements would not cut it. The report defined what it meant by this newly coined term, which was identified it as one of the six core aims in improving healthcare:

“Patient-centered: providing care that is respectful of and responsive to individual patient preferences, needs, and values, and ensuring that patient values guide all clinical decisions.” (IOM, 2001)

In a system where, of the four participants—the provider, the payer, the employer (or government agency) and, oh, yeah, the patient—the one whose health is at stake has historically had the least voice in the discussion, recasting that dynamic from “patient/pawn” to “patient-centered” is a change of Vesuvian proportions and potentially equally Vesuvian results. But it is a change whose time definitely has come.

Immersed in a burgeoning digital society spurred by technological innovation at the turn of this century, people began to have heightened expectations for transparency, customer service, being informed, and having choices. This newfound power began to drive customers to look for alternatives to their traditional sources of care and where they get their information about their health and well-being.

Combine the vast expansion of available health and wellness information opened up by the internet with the relentless increases in the proportion of individual spending going into healthcare, and a change—indeed a revolution—was inevitable.

As consumerism in healthcare began to gain momentum over the past decade, overall dissatisfaction with the healthcare experience, its disappointing outcomes and its high costs had begun to change the meaning of value from the perspective of the patient/consumer. Patients pushed back on the traditional paternalistic system that says that health plans, payers, health systems and other providers know what is best for them.

Should we believe them? Do consumers really know what’s best for them, and should the industry be restructuring itself to give them the power to make those decisions?

Perhaps a historical precedent could be useful before we throw a ticker tape parade for value-based care.

In 1978, Congress upended the norms of retirement saving in the United States with the creation of the 401(k) program. It too was positioned as empowering the individual. Unfortunately, the system did not end up being used the way its creators intended and many early thought leaders in the movement now regret having led the charge. What happened, and are there useful insights (or warnings) to come from that process?

Most of the unforeseen shortcomings emerging from the move to give consumers more control over their retirement saving process stem directly from the behavior of consumers. Many people who participated in 401(k) programs did so thinking they would suffice to cover their retirement. Sadly, many more—through bad advice, shortsightedness or just lack of fiscal discipline—didn’t even do that. Today, it is widely acknowledged that many baby boomers do not have sufficient savings to fund their retirements. It turns out that giving power to the consumer can have one fundamental flaw to it: many consumers don’t know what to do with their newfound power and they frequently don’t use it as it was intended. The change can be a benefit to some but it can also be a disaster-in-waiting for others.

What Exactly is “Value” Anyway?

Nonetheless, if we can agree that the shift to patient-centered care—where we remove the dunce cap that the industry has historically placed on the patient and invite him or her into the clinical value discussions—is a change whose time has come, we are left with two questions:

- Who, in this new alignment of power, will be the final arbiter of “value;” and

- How will we get from here to there with as few 401(k)-like unforeseen problems as possible?

The “value” in value-based care means different things based on whether you ask an employer, a health plan administrator, a government payer, a provider or a consumer. It is true that our healthcare system is bloated, inefficient, expensive, and fragmented, making it an imperfect platform for delivering high-quality outcomes for patients. It is possible from various points of view in healthcare to paint everyone as a villain in this:

- Patients say providers do not give them the time and attention they need to serve their needs and provide the outcomes they desire. Providers say this is because they have to spend a majority of their time complying with reporting requirements from the government and insurance companies so they can receive reimbursement.

- Employers want more alternatives for their employees at the same time that the premiums health insurance companies charge climb higher and higher. Employers also want providers to be more accountable for their outcomes, while lowering their treatment costs and increasing their efficiencies.

- Health insurers are blamed for surprise bills and high out-of-pocket costs.

- Health insurers are also blamed for the heavy-handed rejection of reimbursement requests and a painful, sloth-like, often intransigent appeal process.

- The government is blamed for all of it at some point, and is expected by the consumer/voter to provide solutions that so far have not been seen as satisfactory.

So, there is plenty of blame going around and no single arbiter of value. Worse still, in the current setting, “value” is largely a financial negotiation between the provider and the payer, with the patient exiled to the waiting room while the judgments about his or her health are made. In terms of trying to create a model ecosystem that is truly patient-centric/consumer oriented, it is perhaps more important to not search for a villain, but to look at who has the power in the current system and who does not and go from there in developing various models.

The question “What exactly is “value” anyway?” is not so easy to get our hands around, it turns out. So as the industry attempts to define value for a pool of 300+ million unique consumers, the final result will likely come down to the issue of who has the power in the defining process?

The adage “money is power” is a good starting point. So let’s look at where power and money reside and how that power is affected in other healthcare systems around the world.

Is There a Useful Model for a Consumer-Centric Healthcare System in the World Today?

In the developed countries of the world there are basically four types of healthcare systems—the Beveridge model, the Bismarck model, the National Health Insurance model, and the Private Insurance model, also known as the Out-of-Pocket model. It is helpful to briefly describe these four models and their relationship to the U.S. healthcare system before we dive into presenting other possible paradigms.

1. The Beveridge Model

Beveridge is a national, single-payer health insurance model that can be found in several countries, including the United Kingdom, New Zealand, Cuba and Spain. It is similar in some ways to the U.S. Veterans Health Administration system. The Beveridge model considers healthcare to be a right for all citizens. In this model, the government is the only payer. Health care is funded by taxes, so there are no out-of-pocket costs at the point of service, and the majority of hospitals and doctors work for the government, although there are some private physicians. Those who espouse the Beveridge model believe that the lack of competition serves to keep costs low for the most part. Benefits are standardized everywhere in the country.

Potential drawbacks of this model are over-utilization of healthcare services, long waiting lists for care and a relative lack of individual initiative expanding the boundaries of care. While opponents of this model cite long waits due to a lack of available physicians, along with prohibitive costs that can bankrupt the system, the data generally show this is not the case. A total conversion to the Beveridge model in the United States would mean the health insurance business would be eliminated, nearly all physicians would become government employees, pharmaceutical companies would become tightly regulated, a host of new bureaucracies would be created at all government levels.

2. The Bismarck model

The Bismarck model is a social health insurance model that can be found in Germany, Japan, Belgium and Switzerland. It is less centralized than the Beveridge model, and it is similar in some ways to our employer-sponsored health plans in the United States. This model is not intended to provide universal health coverage, and it is funded largely by employers and employees. The Bismarck model considers healthcare to be a privilege for employed citizens. Even though healthcare providers in the Bismarck model are mostly private entities, the funding is considered to be public.

A main drawback of a purely Bismarck model is that its resources are focused mainly on people in the workforce who can contribute financially. People who are unable to work and the aging population are vulnerable in a pure version of this model, which is one reason why countries who adopt this model often also incorporate aspects of the Beveridge model. Converting completely to this model would eliminate for-profit doctors and hospitals. Doctors would make less money, but would also leave medical school with little or no debt.

3. The National Health Insurance model

The National Health Insurance model, like the Beveridge model, is single-payer national health insurance, but like the Bismarck model, the healthcare providers are private. This model is found in several countries, including Canada, South Korea and Taiwan, and is similar in many ways to Medicare in the United States. The government processes all insurance claims, generally resulting in reduced duplication of services and lower health insurance administrative costs. Importantly, the universal insurance does not make a profit or deny claims. The balance between public insurance and private healthcare provision means that hospitals and other healthcare providers can remain independent.

A major drawback to this system for patients is that wait times are notoriously long. A drawback for the system itself is over-utilization of healthcare services for non-urgent situations. Converting to this system would be similar in some ways to the Medicare-for-all bills currently proposed in Congress.

4. The Private Insurance model (aka the “Out-of-Pocket” model).

The Private Insurance model is common in less developed areas of China, South America, India and Africa. It is similar to what the millions of uninsured people in the United States experience. The model is simple: those who can afford appropriate health care pay for it out of pocket at the point of care. The obvious drawback is that those who cannot afford appropriate healthcare do not receive it. In the United States, there are large disparities in care due to ethnicity and socioeconomic status. In Massachusetts, for example, the uninsured rate is 3 percent, while in Texas, 17 percent of people are uninsured. In all, approximately 28.5 million people in the United States are uninsured. Converting completely to this model would greatly increase the number of uninsured people in the United States.

Now that we have some background on the most common models of healthcare systems in the world, we can begin to look at what a consumer-driven model might look like. Let us start with what consumers are looking for.

What do Healthcare Consumers Want?

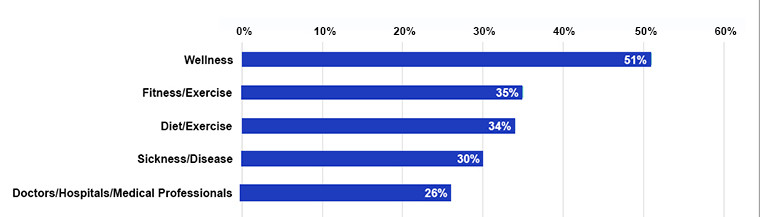

The first thing we need to know to be able to illustrate the consumer-driven landscape is what consumers believe they want. A 2017 study of 1,509 U.S. adults who had engaged with health-related information online during the past 12 months asked this question: “When you hear the word ‘health,’ what are the first words or characteristics that come to mind? (See Figure 1). Respondents could select up to three choices. The first choice, by far, was “wellness” at 51 percent, followed by “fitness/exercise” at 35 percent and “diet/nutrition” at 34 percent. It was not until the fourth item that “sickness/disease” came up, at 30 percent, followed by “doctors/hospitals/medical professionals” at 26 percent.

Figure 1: What do you think of when you hear the word “health?”

Source: (Brightline Strategies, 2017).

So, it would appear that when consumers think of health, they are envisioning getting well and staying that way. That also sounds like consumers are looking to move away from our old acute-care, volume-based brand of health care. They do not know how to make that a reality, but they are signaling what they want it to look like.

For most healthcare interactions, you need three things: a patient, a provider, and medical information that is relevant to that patient. Since these three things are necessary, how can just one of them (the patient) be at the center of the encounter? The patient/consumer does not necessarily think about wanting to be in charge of the healthcare system or at the center of it. They just want changes in it, and that is out of their hands. That sounds like a “customer satisfaction” issue.

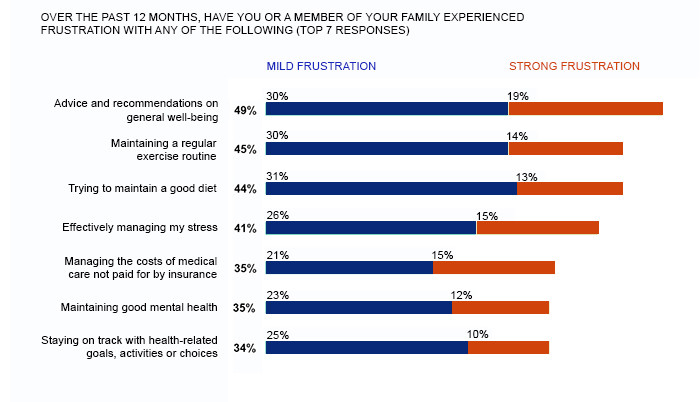

An online survey with 2,509 responses taken in July 2018 by the global management consulting firm Oliver Wyman took the “What does health mean to you?” question a step further, prompting consumers to identify their frustrations about their general physical and mental well-being. The top seven frustrations are listed in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Top frustrations with physical and mental well-being.

Source: (Rudoy, Bernene, Glick, Leis & Michelson, 2018)

The study authors noted that they expected cost and convenience to be high on the list of frustrations, which they were, but cost came in at number five, as you see above, and convenience did not even make the top 10. Note that all of the other issues in the top seven address either preventive care or wellness.

You should also notice that these unfilled expectations, generally speaking, go beyond the services that hospitals, health systems and other traditional healthcare providers are set up to currently provide for consumers. There are websites that can help people with some of these issues to some degree, and there are apps that can partially help with some of the others, but so far, most provider organizations are not in this picture.

Our healthcare system is generally set up well for acute care but not for wellness. Is it possible for providers to shift to delivering care along a “Wellness Continuum” that is consumer-directed? THAT would be a gigantic disruption to historical norms! But if a total consumer-focused disruption is not possible in healthcare, can we design an experience that gives them much more of what they want, rather than giving them what we currently produce?

What Does a Consumer-centric Healthcare Ecosystem Look Like?

If a total consumer-focused disruption is not possible in healthcare, can we design an experience that gives them much more of what they want, rather than giving them what we currently produce?

There is a central question in all of this: Who is the customer?

Employers and the government have historically been the primary funders of healthcare in this country, so providers and health plans have traditionally looked at employers and the government as their customers. The patient’s needs were considered by providers and health plans through that lens. For example, take Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) Scores (originally called HMO Employer Data and Information Set). At the outset, HEDIS scores purported to help consumers compare health plan performance. In reality, HEDIS scores were used to a great extent by HR departments to work with their insurance company partners to increase efficiencies and largely to increase margins.

Again, we don’t want to demonize anyone. We first want to get at who has the power and who does not. In the retail world, which is truly consumer-oriented, the consumers are the most powerful people in the ecosystem. Not so in healthcare. Remember that consumerism began in healthcare largely because of patients feeling they were powerless to control their healthcare costs and outcomes. It is clear that in our current model, providers and consumers are the entities that have the least power. But to have a truly consumer-centric healthcare ecosystem, that has to be flipped onto its head.

For most healthcare interactions, you need at least two things: a patient and a provider. Since these two things are necessary, how about we start with a healthcare ecosystem that includes only those two entities with the least power. But you might ask, if there is no health insurance, where would they get their health care? At the most basic level, what you need in a healthcare model is access to health care and a way to be able to pay for it. How about replacing healthcare insurance coverage with direct primary health care?

Let’s say in our first hypothetical model, that we take health insurers completely out of the picture and then only leave government in the picture for those now in government programs like Medicare and Medicaid.

What if 60 percent (the whole country except for those in government programs) of the people went from the employer-driven model to a direct-care model? Imagine that. In a direct care model, there are no insurers. Either individual providers or groups of providers provide care for a monthly fee and would negotiate rates with specialty and emergency care with hospitals, health systems and specialty providers.

In our next article in this series we will put the power entirely in the hands of consumers and providers, as we present our first hypothetical model: Direct Primary Care.

References

Brightline Strategies. (2017). Consumer health online: 2017 research report. Commissioned by dot.health, LLC. Accessed at https://get.health/research.

Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation (2018) 2017 health insurance coverage of the total Population. https://www.kff.org/other/state-indicator/total-population/

Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality Health Care in America,. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Rudoy, J., Bernene, C., Glick, S., Leis, H., Michelson, J. (2018). Waiting for consumers: The Oliver Wyman 2018 consumer survey of US healthcare. Oliver Wyman, Marsh & McLennan Companies. Accessed at: https://www.oliverwyman.com/content/dam/oliver-wyman/v2/publications/2018/october/Consumer-Survey-US-Healthcare.pdf