Healthcare Consumerism and the Move Toward Wellness

A Four-Part Series by Will Stabler

About This Series

I wrote this article series 2019 as consumerism was presumably taking hold in the healthcare industry. The series examines several potential models for a consumer-centric healthcare system.

Articles in This Series

Consumer-Centric System #2: The Patient Engagement Model

By Will Stabler

First published on Feb. 5, 2019

In our previous hypothetical consumer-centric healthcare system model—direct primary care—we took the power away from the two most powerful entities in our healthcare system—employers and health insurers—and put it into the hands of the least powerful—consumers and their providers. In doing that, did we over-presume that what consumers truly want is power—calling the shots, being in charge?

Healthcare Ecosystem #2: The Patient Engagement Model

In this next hypothetical consumer-driven model we explore another possibility. What if we presume that consumers do not really want to be in charge of their health care? Assume instead that consumerism in healthcare is more about people just knowing what they want (and wanting what they want) out of the healthcare system, and power is not one of the things they want.

Before we look at a national single-payer model (in our next article) or a free-wheeling private health insurance market in the article (after that), let’s look at a multiple-payer system in which we keep private health insurers and employers working together in the driver’s seat. This sounds much like the system we have now.

Can a healthcare system similar to the one we have now progress into giving consumers everything they want, while still staying financially viable? Perhaps, but not without with some major tweaking of the roles of health insurers, employers and consumers. First, let’s take a look back at how consumerism in health care has evolved and where it’s heading.

When people think of consumerism in this space, they often think of being able to shop around for healthcare services and health insurance plans, but there is so much more to it than that. It is helpful to go back to some key principles in the 2001 Institute of Medicine (IOM) report “Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century,” which opened the 21st century by explaining how healthcare needs to change. Many of the foundations of consumerism are contained in the concepts the IOM espoused. They also lay a framework for seeing where we are now.

The IOM committee formulated a set of 10 general principles—they called them rules—for redesigning the healthcare system. Of those 10 rules, half of them directly relate to drivers of consumerism in health care:

- Care is based on continuous healing relationships.

- Care is customized according to patient needs and values.

- The patient is the source of control.

- Knowledge is shared and information flows freely.

- Transparency is necessary.

According to the IOM report, embedded within these five rules above are concepts such as patients having:

- care available whenever they need it, and not necessarily face-to-face

- customized care based on their choices and preferences

- sufficient information so they can control healthcare decisions that affect them

- detailed information on safety, evidence-based practice and satisfaction that inform their decisions about choosing a health plan, a hospital, a provider or alternative treatments

- unfettered access to their own medical records and to clinical knowledge (IOM, 2001)

Take note (and this is starting to become a theme in this series) that all of those last five bullets describe healthcare system transformation goals that can be met through innovation in health information exchange and interoperability.

So, What is at the Heart of a Consumer-centric Healthcare System?

As we noted in our first article, our historically paternalistic system is a long way from the kind of patient-centered care outlined in the bullet points above from the IOM report. To get there it will need to start involving the consumer in more meaningful ways.

Perhaps what consumers want is not power at all, but RESPECT—care customized for their needs, care available when and where they need it, access to their medical records, and enough information to inform their decisions about health plans, hospitals and providers.

The hypothetical model of consumer-centric healthcare we are presenting here starts out based on our current system, but adds this element of respect. We will call this the Patient Engagement Model, which is based on a strong belief that patients can and should make informed decisions about their healthcare if they choose to do so. And they should be empowered and enabled to do so.

Consumer-centric healthcare systems are not going to be driven by people who sit on the sidelines, so before we address what consumers want, it is important to define what makes an engaged consumer. A 2016 Deloitte survey of consumer priorities sums it up well: “The engaged healthcare consumer is proactive about their care management and cost considerations, and takes the time to understand larger aspects of the health care ecosystem that pertain to them. Therefore, consumers are increasingly expecting more out of the services they receive from their providers” (Read & Kaye, 2016).

Let us look at major categories of what engaged consumers are seeking. According to the Deloitte study, the main things these engaged consumers want are:

- greater personalization of the healthcare experience from providers

- transparency in network coverage, medical prices, and bills

- convenience

- more engaging digital experiences and capabilities (Read & Kaye, 2016)

In our Patient Engagement model, providers, hospitals, health systems and accountable care organizations have a role in making it work. They must continue to move toward a more personalized, preventive, wellness-based mode with consumers, minimizing readmissions and setbacks, improving the experience for them, and guiding them toward the behaviors that can keep them healthy. That will take time, and I am not talking about the time it will take in years to accomplish it. I mean it will involve providers taking much more time with each patient than most of them are able (or willing) to commit to in today’s environment. This was one of the main benefits of our first model—direct primary care.

Where are we at With Transparency?

Providing information that is relevant and transparent to the consumer will be key to any type of consumer-centric transformation of the healthcare system, and transparency is currently a problem throughout our healthcare system. If our Patient Engagement Model is to be successful and financially viable, consumers will need better information to inform their choices than they have now. When discussing cost transparency in health care there are two areas to be considered—costs of provider services and the cost of insurance plans. Both have a direct impact on the consumer, but they are two very different animals, involving differing motivations, structures, and impacts on the consumer. These are two distinct categories of costs, because the processes of controlling them and the parties involved are very different indeed.

Provider Transparency

Transparency in healthcare provider costs is vital to a consumer-centric system, where the patient is engaged in shared decision making with the provider in a cost/benefit analysis in making medical decisions. In our current system, the doctor is incentivized to choose whatever solution gives the greatest likelihood of success regardless of cost, with the patient out of the discussion.

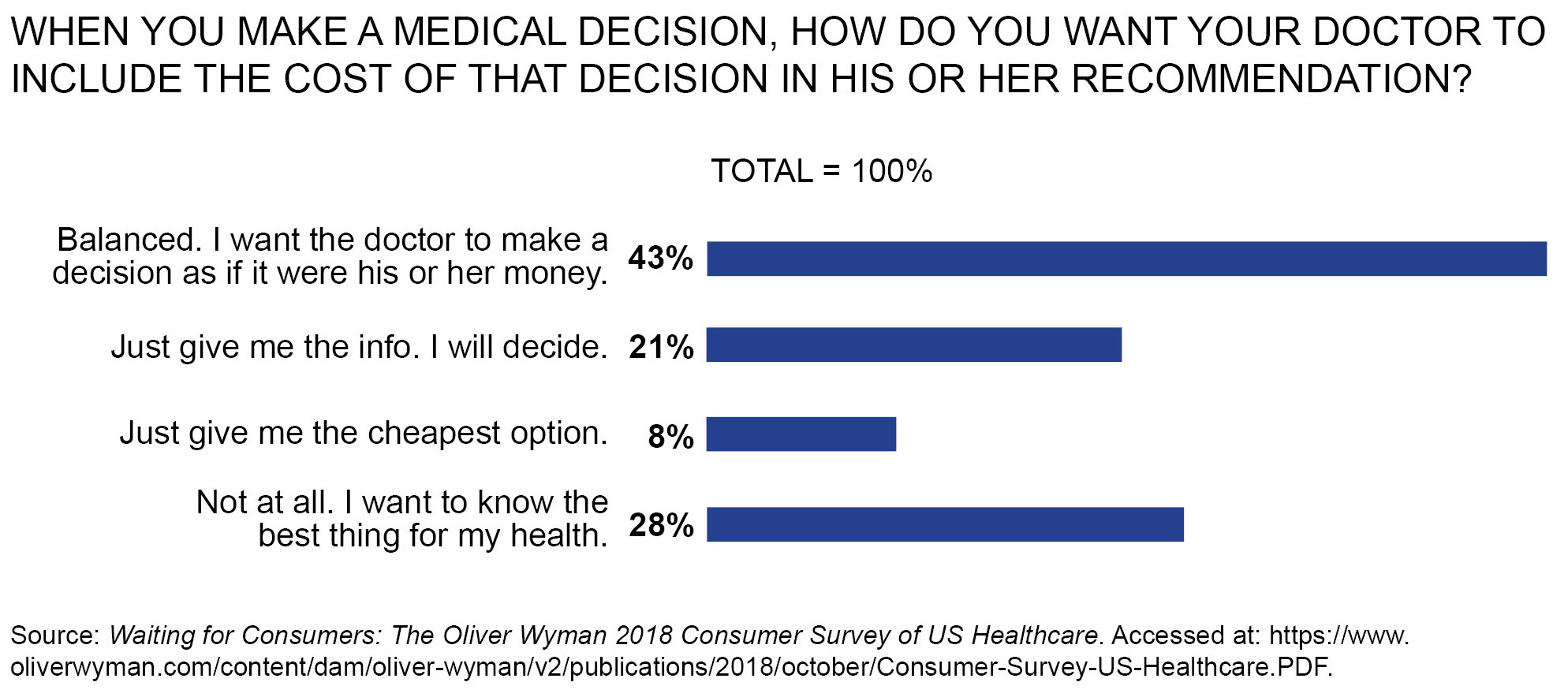

Apparently, this old paternalistic brand of decision making is not what consumers want (See Figure 1). In a July 2018 online survey by the global management consulting firm Oliver Wyman with 2,509 responses, a plurality of consumers (43 percent) indicated they wanted a more balanced approach (Oliver Wyman, 2018).

Figure 1: Consumers Want Doctors to Consider Costs

As you can see, the way things generally work with medical decisions in our current paternalistic model still ranked second, but this survey found that younger respondents preferred the balanced option over older respondents, perhaps indicating change is happening. To employ that first option, doctors will need to engage their patients more in the clinical decision-making process and also be more transparent about what the real costs are.

Although much is made of cost transparency in healthcare consumerism, it is just one example of where there are significant relevance and transparency challenges. A 2018 report brief from Rice University’s Baker Institute for Public Policy analyzed the literature and addressed transparency as it relates to healthcare consumerism.

“We live in a world where an individual’s discretionary choices (food, clothing, travel) are increasingly driven by convenience and amenability to control—e.g., online shopping—and the prevalence of mobile apps,” the researchers wrote. “These attitudes will only heighten with future generations and it should come as no surprise that they greatly influence how people interact with the healthcare sector” (Offodile & Ho, 2018).

At the same time, those researchers expressed concerns over the level of transparency in provider costs in health care, how health literacy is facilitated, and how competition affects the evolution of these trends. “It is clear that quality and cost data need to be labeled and disseminated in a format that is easy to understand, actionable, and minimizes misinterpretations,” the report authors argued. “In other words, at the point of purchase, patients should be provided with the tools to enable them shop around for the care that best serves their needs” (Offodile & Ho, 2018).

A 2018 report from Solv and the Urgent Care Association of America found that while 70 percent of people look for prices before a healthcare visit, only 23 percent of them actually receive prices after asking for them, and 48 percent of them “feel stupid” for asking. The same study found that 68 percent of older Americans don’t believe healthcare price information is available, and even among younger people, only 50 percent believe it is available (Solv & UCCA, 2018).

That’s because, for the most part, it isn’t available. The Solv study found that even among convenient care providers, most of whom do have prices available, only 17 percent list those prices publicly.

“Much of the reason that this information remains unavailable to consumers is because providers fear penalties from payers,” the study authors wrote. “In fact, convenient care operators often cite that they are contractually obligated to not disclose their negotiated rates and concern that sharing cash pay rates would put them in violation of their agreements” (Solv & UCCA, 2018).

Also, if the consumer’s needs were driving the healthcare industry, wouldn’t cash would be king? Shouldn’t there should be a true, publicly available, non-inflated “chargemaster” at our nation’s hospitals, health systems and providers?

Since the beginning of this year, the Affordable Care Act has required all hospitals to publicly disclose such a chargemaster, which includes: making a list of their current standard charges publicly available online; updating it at least annually, or more as necessary; and listing standard charges in a “machine readable” format. Time will tell whether these disclosures are in a consumer-friendly format that the average person can understand and relate to their medical decision making.

Let us be clear here—cost transparency is NOT telling the patient the cost of a surgeon’s service seconds before the scalpel appears. Nor is it useful for the surgeon or the primary care physician to cite their costs alone. Part of consumer frustration is being told their procedure will cost $X only to find out that there are numerous other players who will submit bills and various other kinds of charges, (e.g., for an organ or a pacemaker) that the patient should have known about. Consumers do not care how much the engine costs—they want to know what the car with the engine is going to cost.

Health Insurer/Employer Transparency

When it comes to transparency, health insurers and their employer partners, like providers, also face challenges in presenting information that is easy to understand and allows consumers to make informed decisions about their health care. But those decisions are much different in this realm, relating to the balance of coverage and how much financial risk consumers are willing to take on. The issues surrounding health insurance decisions are a little more complicated to assess than they are on the provider side.

For example, take high-deductible health plans (HDHPs). In the Oliver Wyman study mentioned earlier, the researchers described two types of insurance approaches and asked respondents to choose. Half of the respondents said they preferred a plan with higher upfront costs and lower out-of-pocket costs guaranteed during the course of a year, while only 21 percent preferred a pan with lower upfront costs and higher out-of-pocket costs throughout the year (Oliver Wyman, 2018).

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 40 percent of people are covered through HDHPs. There is a big disconnect here. Consumers are paying for something they clearly do not want. Are their choices being limited by their employers or the high cost of traditional plans, or are consumers not sufficiently informed on what they are buying? The answer is not clear.

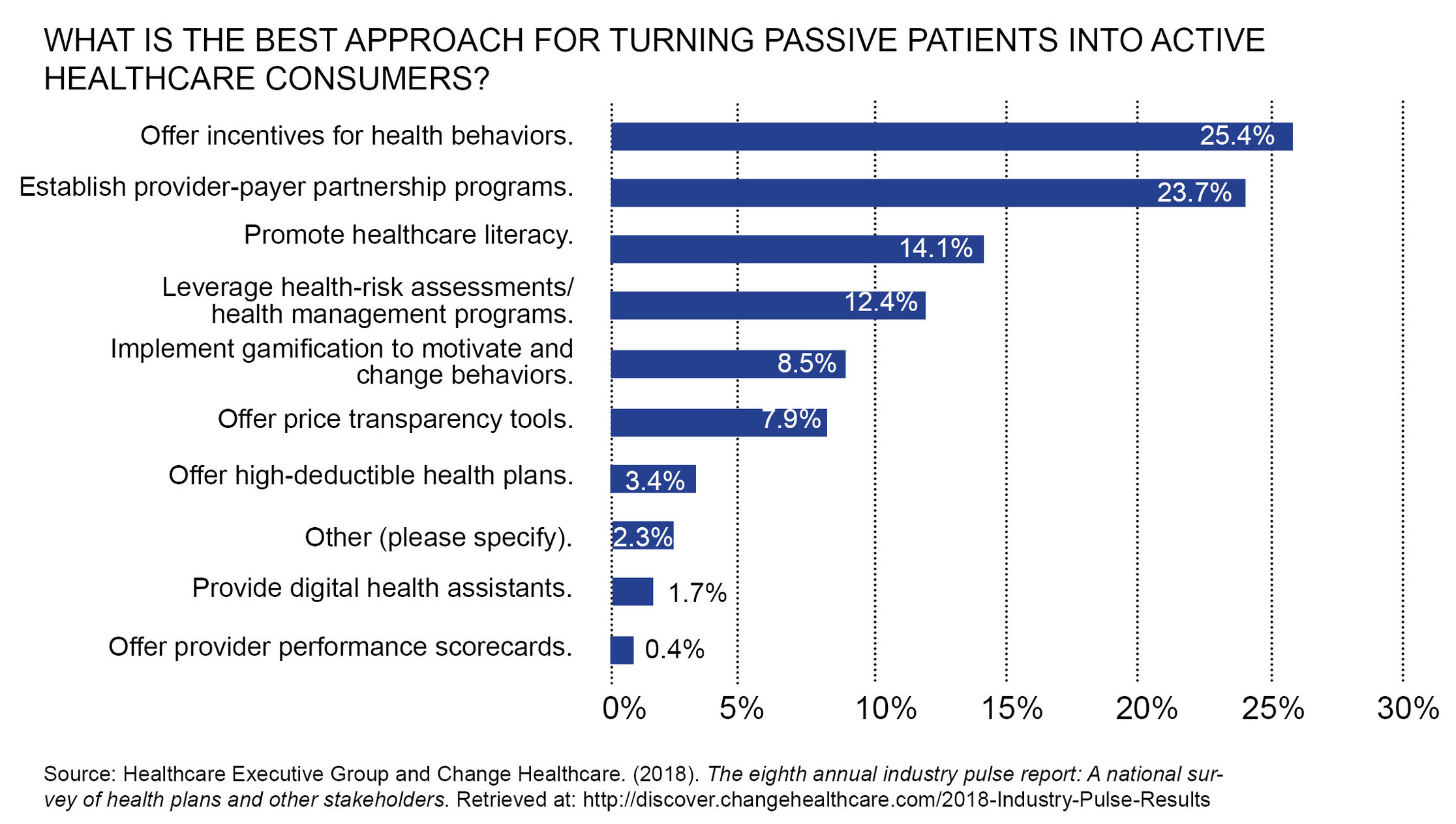

In a 2018 national survey of leading health plans and other healthcare stakeholders commissioned and conducted by the HealthCare Executive Group and Change Healthcare, researchers found that HDHPs were not creating active consumers. Quite the contrary, HDHPs were making them avoid necessary care, rather than spurring them to shop around (HealthCare Executive Group & Change Healthcare, 2018).

In that study, respondents were asked, “What is the best approach for turning passive patients into active consumers?” Figure 1 shows the breakdown of the top approaches.

Figure 2: Approaches for Changing Consumer Behavior

You can see that HDHPs were way down the list. It seems the carrot is mightier than the stick when it comes to creating a consumer-centric healthcare ecosystem, and engaging the patient is the key.

In the Patient-Engagement Model, health insurers would need to come up with health plans that are standardized and communicate them plainly enough so that consumers (and employers) could easily see differences in premiums and coverage among similar plans from different insurers. Employers would need to help insurers in consumer engagement by communicating plan offerings and what each plan means to their employees more plainly and in terms of potential real-life financial consequences of their choices.

Health insurers also need to find ways to structure contractual agreements with providers that remove barriers to provider organizations being transparent with their costs (as mentioned before with the convenient care providers), and employers need to be involved in this process so they can guide decision-making for their employees.

Even if all of this transparency were put into place and consumers had highly detailed, transparent coverages, services and costs were readily available to them, would consumers understand what they were looking at enough to make informed decisions and compare? Even if the transparency piece is solved, there is another barrier caused by our extremely complex health system—consumer health literacy.

Consumer Health Literacy is a Significant Barrier

Transparency seems to be only half the problem when it comes to consumers getting the information they need to make informed decisions about their healthcare coverage and healthcare providers. Even when provider and payer organizations strive for transparency, the low level of health literacy among consumers gets in the way. People need some degree of health literacy if they are going to be able to understand how to shop, and they need to be helped out by those in health insurance and provider segments of the industry.

In a recent study from Accenture titled, “The Hidden Cost of Healthcare System Complexity,” researchers found that 33 percent of healthcare consumers have no experience with healthcare systems, and 19 percent of U.S. healthcare consumers are novices. Those who have low healthcare system literacy need more customer service support, and the people with the highest healthcare need are usually the ones who need the most help navigating the complex world of health plan options and health insurance coverage, according to the study (Stephan, McCaghy, Brombach, 2018, Sept. 6).

These realities come at a high cost for health insurers. The Accenture study authors wrote: “The U.S. healthcare system is so complex that more than half of consumers do not understand how to navigate it appropriately. This low healthcare system literacy is creating an estimated $4.8 billion annual administrative cost burden for payers.”

That sounds like a nice target for improvement and potential cost savings for health insurers, especially considering that consumers with low health system literacy cost payers $4.82 billion in annual administrative costs, while people with high literacy only cost them $1.41 billion—a difference of $3.41 billion annually. Education would seem to be the key to flipping this problem, but according to recommendations from the study authors, education is only one piece. They recommend the following:

- Align information-delivery methods with the behaviors and communications preferences of consumers, directing service options and experiences across physical, digital and emerging channels.

- Deliver personally customized, easy-to-follow programs and relevant products using data insight from advanced analytics and artificial intelligence

- Provide incentives for providers to help consumers understand and navigate health insurance options, and encourage employers to increase health insurance education.

- Use lay navigators—community members who are trained to empathetically help people manage non-clinical challenge, including financial, logistical, emotional, cultural and communication-related (Stephan, McCaghy, Brombach, 2018, Sept. 6).

Who Can Make It Happen?

As we noted before, although consumers are driving what is being described as a transformation toward a consumer-centric system, both consumers and the multitudes of us who work in healthcare have to work together to make it happen. We all have our work cut out for us.

If patients want to become true consumers and eventually get what they want from those in charge of the healthcare system, they will need to take some individual responsibility over how healthcare resources that directly relate to them are utilized. This means starting with shopping for the healthcare insurance coverage that is most appropriate to their needs and circumstances. Are they motivated by the current healthcare ecosystem to do this? Do they want to take the time to shop around for the best price when it comes to health insurance coverage and healthcare services? Can they be the main drivers of quality and cost?

If patients want to become true consumers and eventually get what they want from those in charge of the healthcare system, they will need to take some individual responsibility over how healthcare resources that directly relate to them are utilized.

To facilitate this, health insurance companies would have to start marketing more one-on-one to consumers and their priorities. In an article identifying key trends in healthcare marketing for 2018, Ken Robbins, CEO of Atlanta-based digital marketing agency Response Mine Health, wrote: “Insurance coverage changes are accelerating with higher deductibles, plan terminations and à la carte plans becoming the norm. Consumers are directly impacted by these actions and are becoming more price-sensitive to the services that they are paying a larger percentage of the cost to receive. The complex rules and exceptions are creating confusion and drawing patients to providers that navigate this landscape for them and are able to quote simple ‘driveaway’ prices (Robbins, 2017).”

Price-based shopping is not possible when the underlying attributes of the goods are not consistently defined. The only reason we can compare mileage in cars is because they all define them using miles and gallons as the measure. What the system needs is for someone to devise a standard set of policy terms against which all insurance providers bid. And then we probably need a regulator to stand in and ensure that the insurance companies all conform to those same standards, and pay out on the same formula or pattern.

At the same time, the proliferation of health-related apps is astounding. According to a Research 2 Guidance study, there were 325,000 mobile health apps available in major app stores in 2017, a figure that grew by 78,000 apps from just the year before. In that same study, 53 percent of digital health practitioners believe that health insurers have the best market potential for being the leading distribution channel for health apps in the future.

Everything taken together means the health insurance industry and employers need to work together to improve the healthcare digital experience for consumers, who say they want it to feel more like what they experience in retail. NTT Data conducted an online study in September 2017 that elicited responses from 1,102 U.S. healthcare consumers (NTT Data, 2017). The study sought to find out:

- How satisfied are consumers with the digital customer experience across healthcare companies?

- Where could physicians’ offices or healthcare insurers provide more seamless care?

- How do consumers prefer to interact with healthcare organizations?

More than three-quarters say the digital healthcare experience needs to be improved, and especially that it lacked ease of use and specific features. More than two-thirds say they expect their health insurers, “to make it easier to navigate affordable care and wellness options.”

The following are the six areas consumers in the NTT Data study said needed the most improvement:

- Searching for a physician or specialist (81 percent)

- Accessing a family member’s health records (80 percent)

- Changing or making an appointment (79 percent)

- Accessing test results (76 percent)

- Paying bills (75 percent)

- Filling a prescription (74 percent)

And for the medical providers out there, 50 percent of the respondents said they would change providers for a better digital experience, so health insurers and employers should take this into account in their marketing and educational efforts (NTT Data, 2017).

And let’s not forget employers. In a consumer-centric healthcare system, employer strategies around covering their employees would need to change. The old/current model, in which HR departments work with insurance companies to increase margins and keep employer costs down, does not work well in the consumer/wellness model. In this new world, consumers would design healthcare coverage and delivery that benefits them most, and employers would need to keep up with their wants and needs so they could continue to recruit and keep the best people.

If our current system is going to be both consumer-centric and sustainable, then consumerism has to be a driver of costs, and it needs to drive them drastically in a downward direction. Can consumers do that?

Health insurers have already taken steps in this direction with their HDHP plans. These plans can serve to force the consumer to take more responsibility for their healthcare services utilization. While the growth of HDHPs has slowed somewhat in the past few years, can continued growth in these plans help steer consumers toward utilizing lower cost services, while not discouraging them from more utilization in preventive and wellness areas?

In a 2018 Rice University issue brief on healthcare consumerism, researchers pointed out the intended opportunity of HDHPs: “By shifting the ‘first dollar risk’ through these structures to patients, the hope is that they will become more conscientious and engaged in decisions about which drugs (generic vs. name-brand), treating clinician (specialist vs. primary care), or treatment setting (inpatient vs. outpatient) is the most appropriate to use,” the researchers wrote. “In theory, this should help check health care costs by incentivizing the use of lower-priced options and reducing unnecessary variations in health care utilization” Offodile & Ho 2018).

Here again, we as planners must be vigilant about the risk of unintended consequences. First, is it sensible to think about shifting costs, e.g., through HDHPs, without making commensurate shifts (in advance) in the supply of data and information that would enable consumers to evaluate and control their new responsibilities? There is a fairly simple way to describe the process of shifting costs without shifting the new payer’s ability to manage those costs: theft.

In addition, we want to be careful that we are not incentivizing people to avoid the care they need. Whether the health coverage design is HDHP or a hybrid that serves as a bridge—such as is needed in a direct primary care model—health coverage incentives should drive consumers to innovation, choosing potentially lower cost methods of care provision that satisfy their expectations of what health care should be, and meet their wishes for preventive and wellness care.

Summary

I want to reiterate some of the pros and cons of the Patient Engagement Model in order to summarize.

The following are some of the pros of our Patient Engagement Model:

- Engaged, informed consumers will have higher-quality information on which to base their medical decisions and choices of health plans.

- Consumers who are incentivized toward positive heath behaviors will create a system that emphasizes wellness over acute care, with the result being better outcomes.

- More engaged and informed consumers may help drive down costs by choosing less costly modes of treatment and monitoring.

- Solving our current health literacy problems in this country has the potential for significant cost savings for health insurers.

The following are some of the cons of our Patient Engagement Model:

- Health insurers may be forced to take on more risk if consumers are unwilling to do so.

- Providers will need to restructure their medical decision-making strategies (e.g., through shared decision making, motivational interviewing and employing patient-reported outcomes). This will take considerable work and restructuring and will result in lower patient volume and possible lower reimbursement.

- Health insurers would have to incentivize providers to spend more quality time with their patients over increased patient volume in order to create more patient engagement to achieve the better wellness outcomes consumers want.

- Health insurers and employers need to do much work and investment in developing health plans that are standardized and comparable, and communicating them plainly enough so that consumers will understand what they are paying for, and what the financial and wellness risks are in choosing one plan over another.

- Intensive patient engagement in the health insurance industry would require significant increases in marketing-related expenditures.

- Hospitals, health systems and providers need to provide actionable information for consumers on “whole enchilada” costs for common, and not-so common procedures.

- Considerable capital investments will need to be made in healthcare information technology and interoperability to improve the digital experience for healthcare consumers.

- Hospitals and health systems must continue to decentralize provision of care to provide the convenience consumers want while also controlling costs.

- This system does not solve the problem of the millions of people who are uninsured in the United States unless lower overall healthcare system costs are significantly reduced by it.

Again, this hypothetical model of a consumer-driven healthcare system is not so hypothetical, because it is similar to how healthcare is covered and delivered currently, and we know the cons—ever-increasing costs, people being left out of coverage, and a focus on volume and acute care rather than prevention and wellness.

Things are changing, but the solution in making this model consumer-centric is literally a down-to-earth customer satisfaction/quality improvement adage: don’t give them what we are selling—give them what they want. They want the healthcare experience to be more personal and personalized, they want the system to be up-front about how much care and coverage is costing them, they want convenience, and they want the healthcare system—i.e., insurers, employers and providers—to catch up to 21st century retail when it comes to the digital experience and effective use of their data.

In this model, employers will still want to keep premiums from rocketing out of control while providing more of what their employees want, and health insurers will still want to improve their margins. Any system needs to facilitate the process of getting costs under control or it will not continue to be sustainable, and more and more people will fall through the cracks.

A more consumer-centric version of this model may be viable if employers and health insurers are able to incentivize consumers to move quickly toward the things they want, because many of the things they want—such as staying well and out of the hospital, and moving more toward alternative forms of care—have the potential for substantial cost savings. It will take a monumental shift on the part of health insurers and employers more toward education and digital transformation to get there.

In the next article we turn it all around by exploring the pros and cons of the Medicare-for-All proposals in the Congress and what other similar systems around the world experience in such models.

References

Betts, D., & Korenda, L. (2018) Inside the patient journey: Three key touch points for consumer engagement strategies. Findings from the Deloitte 2018 health care consumer survey. Deloitte Development, LLC Retrieved at: https://www2.deloitte.com/insights/us/en/industry/health-care/patient-engagement-health-care-consumer-survey.html

Committee on Quality Health Care in America, Institute of Medicine. (2001). Crossing the quality chasm: A new health system for the 21st century. Washington, D.C.: National Academy Press.

Kaiser Family Foundation. (2018). Employer health benefits 2018 annual survey. Retrieved at: http://files.kff.org/attachment/Report-Employer-Health-Benefits-Annual-Survey-2018

Healthcare Executive Group and Change Healthcare. (2018). The eighth annual industry pulse report: A national survey of health plans and other stakeholders. Retrieved at: http://discover.changehealthcare.com/2018-Industry-Pulse-Results.

NTT DATA. (2018, March 5). NTT DATA study finds nearly two-thirds of consumers expect their healthcare digital experience to be more like retail. https://us.nttdata.com/en/news/press-release/2018/march/ntt-data-study-finds-consumers-expect-their-healthcare-digital-experience-to-be-like-retail

Baker Institute for Public Policy, Rice University. (2018, March 20). Making “cents” for the patient: Improving health care through consumerism. Offodile, A.C. & Ho, V.

Pohl, M. (2018). mHealth app economics 2017/2018: current status and trends in mobile health. Research2Guidance. Retrieved from: https://research2guidance.com/product/mhealth-economics-2017-current-status-and-future-trends-in-mobile-health/

Read, L., Kaye, M. & Patton, A.J. (2016). What matters most to the health care consumer? Insights for health care providers from the Deloitte 2016 consumer priorities in health care survey. Deloitte Development, LLC. Retrieved from: https://www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/us/Documents/life-sciences-health-care/us-lshc-cx-survey-pov-provider-paper.pdf

Robbins, K. (2017, Dec. 20). 9 consumerism trends that will dominate health care marketing in 2018. MHS Newsletter. American Marketing Association.

Rudoy, J., Bernene, C., Glick, S., Leis, H., & Michelson, J. (2018). Waiting for consumers: The Oliver Wyman 2018 consumer survey of US healthcare. Oliver Wyman, Marsh & McLennan Companies. Accessed at: https://www.oliverwyman.com/content/dam/oliver-wyman/v2/publications/2018/october/Consumer-Survey-US-Healthcare.PDF

Stephan, J., McCaghy, L., & Brombach, M. (2018, Sept. 6). The hidden cost of healthcare system complexity. Accenture. Retrieved at: https://www.accenture.com/t20180906T134048Z__w__/us-en/_acnmedia/Accenture/Conversion-Assets/DotCom/Documents/Local/en/Accenture-health-hidden-cost-of-healthcare-system-complexity.pdf