Healthcare Consumerism and the Move Toward Wellness

A Four-Part Series by Will Stabler

About This Series

I wrote this article series 2019 as consumerism was presumably taking hold in the healthcare industry. The series examines several potential models for a consumer-centric healthcare system.

Articles in This Series

Consumer-Centric System #3: Making Medicare for All Work in a Consumer-Centric System

By Will Stabler

First published on March 14, 2019

So far in this article series we have introduced consumerism in health care and then presented two hypothetical consumer-centric healthcare system models. In the first—direct primary care—we gave consumers (and their provider partners) all of the power, presuming that power over the system was what consumers wanted. In the next model—the patient engagement model—we put the power back where most of it is now—with health insurers working together with their employer partners—assuming that consumers do not want that power, and their definition of a consumer-centric system is just getting them the things they want out of the system.

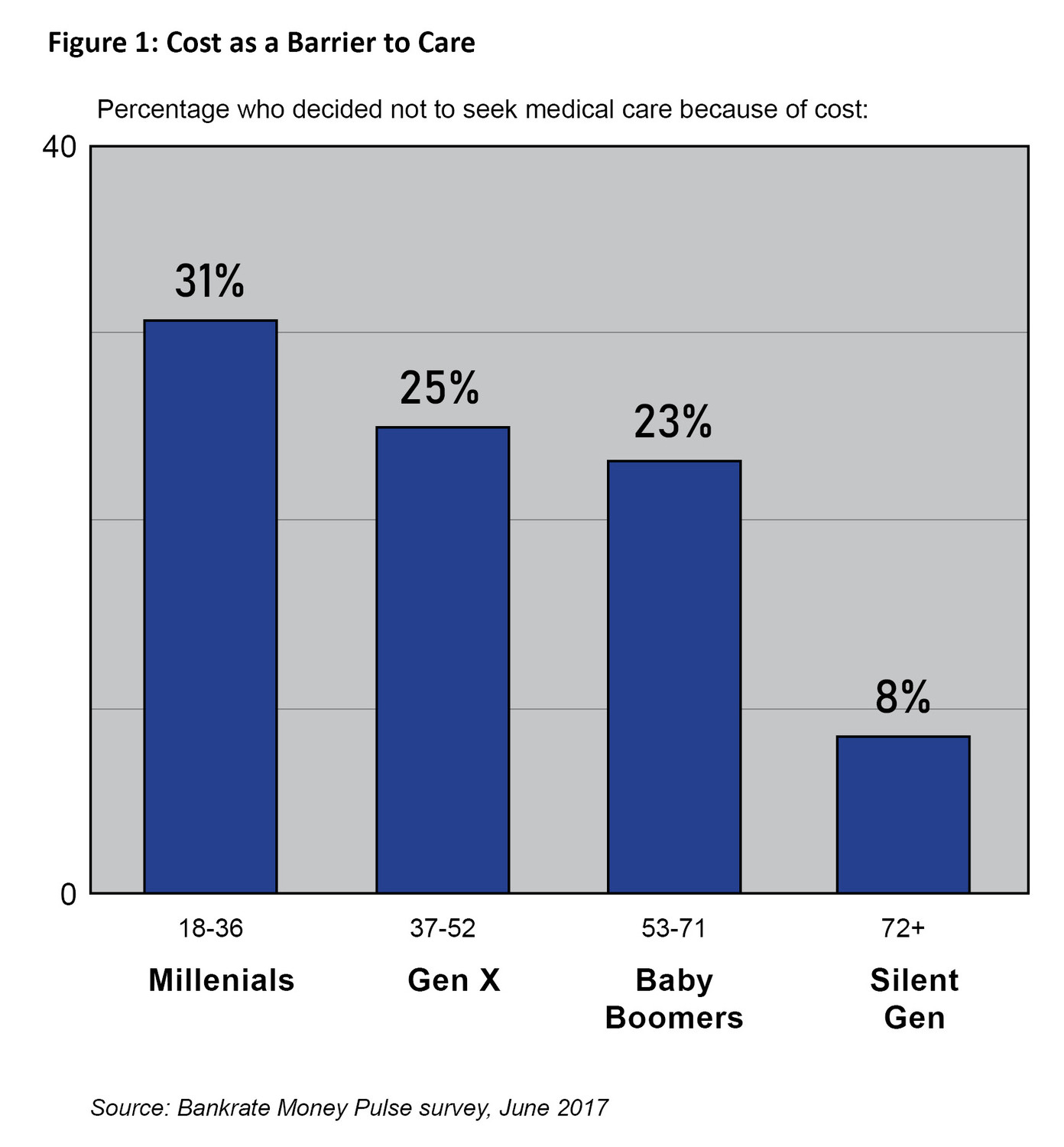

Healthcare Ecosystem #3: Government as the Single Payer

A theme that started early in this series is that what consumers want most is to be well and stay that way. Wellness happens when people are able to get the regular care they need. A 2017 Bankrate Money Pulse survey found that under our current system, a quarter of Americans have made the decision to forgo care due to cost, and older Millennials (ages 27 to 36) are the most likely to forgo care. “About 1 in 3 Americans in that age group say they’ve chosen not to seek needed medical attention because they couldn’t afford it,” according to the study authors (Frankel, 2017). Figure 1 shows how this shakes out generationally.

The same study found that 56 percent of people are worried about their ability to afford health insurance coverage in the future. If those worries pan out, this problem of forgoing care will only get worse.

Wellness is what consumers want, but being forced to place money issues over medical attention is not a prescription for wellness. So, is there another way to get to a wellness-based, consumer-centric healthcare system in this country?

Consider another angle on consumerism in the healthcare system today: How do we end up with consumers driving the direction of the healthcare system when 60 percent of Americans say they believe that government should be responsible for ensuring people are provided with healthcare coverage, and 31 percent believe the system should be single-payer? Those numbers, which have grown since 2016, were part of a Pew Research study that also found that only 4 percent of people believe government should not be involved at all. Even among the 37 percent who say the government is not responsible for coverage, a great percentage of them do not want the government entirely out of it. When asked whether Medicare and Medicaid should be continued, 31 percent overall in that survey said yes (Pew Research, 2018).

Apparently, it is difficult for people to imagine a healthcare ecosystem that does not involve the government to some degree as a payer and a regulator. But what about making the government the single payer?

On January 28, just-announced Democratic presidential candidate Sen. Kamala Harris was asked by an audience member in a CNN town hall, “What is your solution to ensure that people have access to quality health care at an affordable price?”

Harris responded, “We need to have Medicare for All.” When pressed by CNN moderator Jake Tapper whether that means she is in favor of eliminating private health insurance altogether, she first laid out a few of the common problems consumers have with private insurance, including delay in approvals and denial of coverage, and then said, “Let’s eliminate all of that. Let’s move on.” (Luhby & Krieg, 2019)

Looking at National Health Insurance Model Proposals

For this article our hypothetical model will be a national, single-payer health plan. Instead of directly looking at an existing model from another country, we will detail two proposals that are currently in the hopper here in the United States and how their particulars relate to consumers. The first is the single-payer healthcare reform proposal from Physicians for a National Health Program (PFNHP), an advocacy organization of more than 20,000 American physicians, medical students, and health professionals. The second is the Senate bill (S. 1804) titled, “Medicare for All Act of 2017.” The new Democratic majority in the House is crafting its own Medicare for All bill, but it has not been finalized and details are not yet available.

First, both proposals are basically on the same page when it comes to what will be covered, although they have different ways of articulating and providing those coverages (e.g., the Senate Bill leaves long-term care up to state Medicaid plans).

PFNHP states very simply that it would cover all medically necessary services, including mental health, rehabilitation and dental care.

The Senate version would cover the following items and services if medically necessary or appropriate for the maintenance of health or for the diagnosis, treatment, or rehabilitation of a health condition: hospital services including inpatient and outpatient hospital care, 24-hour-a-day emergency services and inpatient prescription drugs, ambulatory patient services, primary and preventive services (including chronic disease management), prescription drugs, medical devices, biological products (including outpatient prescription drugs, medical devices, and biological products), mental health and substance abuse treatment services (including inpatient care), laboratory and diagnostic services, comprehensive reproductive/maternity/newborn care, pediatrics, short-term rehabilitative and habilitative, services and devices, oral health, audiology, and vision services. Critics of the Senate bill say that it should cover long-term care rather leaving it up to state Medicaid programs, and the requirement for co-pays for medications (up to $200 out-of-pocket) should be eliminated.

Both proposals allow people to buy private health insurance, but would ban private health insurance companies from selling plans that duplicate the benefits covered in the national health plan.

The start date of the Senate bill is on January 1 of the first year after passage of the Act and has a one-year transition period for children and a 4-year transition period for adults, during which time any person eligible to receive benefits may opt to maintain their current private health insurance coverage. The Senate version would remain a multi-payer system for the first four years, upon which time it would become a full universal, single payer system.

The PFNHP proposal also outlines a “detailed transition process” and a “transition period” but does not say how long the period would be. Some proponents of Medicare for All oppose a transition period, saying it would result in greater expense and open the door to opposition to full implementation.

Some of the rationale for this transition is explained in the PFNHP proposal: “Implementation will require a detailed transition process and pose novel problems; for instance, significant resources will be needed for job retraining and placement for displaced health insurance and billing workers. But those dislocations would be offset in part by increased employment in care delivery and in other sectors of the economy, since employers would be relieved of the burden of providing ever more expensive health insurance.”

PFNHP also proposes that the national health program fully subsidize the education of physicians, nurses, public health professionals and other healthcare personnel. The PFNHP proposal would compensate physicians and other outpatient practitioners either on a fee-for-service or salaried basis, depending on the situation of the provider.

The Senate proposal allows providers or provider organizations to be investor-owned. The PFNHP proposal would convert for-profit hospitals and health systems to non-profit governance and compensate owners for past investments.

What do the People Think About Medicare for All?

Eskew’s frequently cited study, “Primary Care: Practice Distribution and Cost Across the Nation” identified 141 practices with 273 locations across 39 states. Of those, the study was able to find online pricing for 116 of the practices, and found that the average monthly cost of $93.26 (with a range from $26.67 to $562.50 per month). Of those that charged a one-time enrollment fee in addition to the monthly fee, the average for that fee was $78.39. About a quarter of DPCs charge a per-visit fee in addition to the retainer, which averaged $15.59. The “concierge” connotation we mentioned before might be well-deserved, since this study also found that practices that described themselves as “concierge” providers charged an average of $182.76, compared with an average of $77.36 for those who described themselves as “direct primary care” providers. (Eskew & Klink, 2015).

Overall, DPC arrangements, even when combined with high-deductible, catastrophic, or otherwise low-cost health plans, can be much more affordable than premium health plans, especially for healthier adults, or those not yet eligible for Medicare.

Before we lose sight of the fact that the purpose of this series is to come up with a consumer-centric healthcare system, let’s bring consumers back into our story and examine what they think about the whole idea.

Pundits on the right have branded Medicare for All as socialism, which has long had a negative connotation in our capitalist society. Your interpretation depends on whether you view the term negatively. When the government both pays for and provides the services, such as in the United Kingdom’s system, that is socialized medicine. The United States has socialized medicine with the Department of Veterans Affairs and the armed forces. One could argue that the Senate Medicare for All proposal is only partly socialist, because the government is paying for the services, but providers can remain non-governmental entities, whether non-profit or for-profit. The majority of those on the right also question the feasibility of implementing Medicare for All, with cost estimates in the trillions of dollars, and continue to have doubts that a full government takeover is the right fix for what ails us.

A majority of people support Medicare for All, according to a poll by the Kaiser Family Foundation released in mid-January 2019, which found 56 percent of Americans support a single-payer plan, while 42 percent oppose the concept (Kirzinger, Muñana & Brodie, 2019).

But not so fast. The researchers found that the level of support depended on how they asked the question. According to the researchers, “overall net favorability towards such a plan ranges as high as +45 and as low as -44 after people hear common arguments about this proposal.”

A majority of people support Medicare for All, according to a poll released in mid-January 2019, which found 56 percent of Americans support a single-payer plan. But not so fast. The researchers found that the level of support depended on how they asked the question.

For example, when people were told that Medicare for all would “guarantee health insurance as a right for all Americans,” support for the idea rises to 71 percent. But when they were told that it would “require most people to pay higher taxes,” that support sinks to 37 percent, even though 77 percent of the respondents say they were aware that higher taxes are part of the bargain. So, depending on which arguments they hear, favorability can swing from 71 percent in favor to 70 percent opposed.

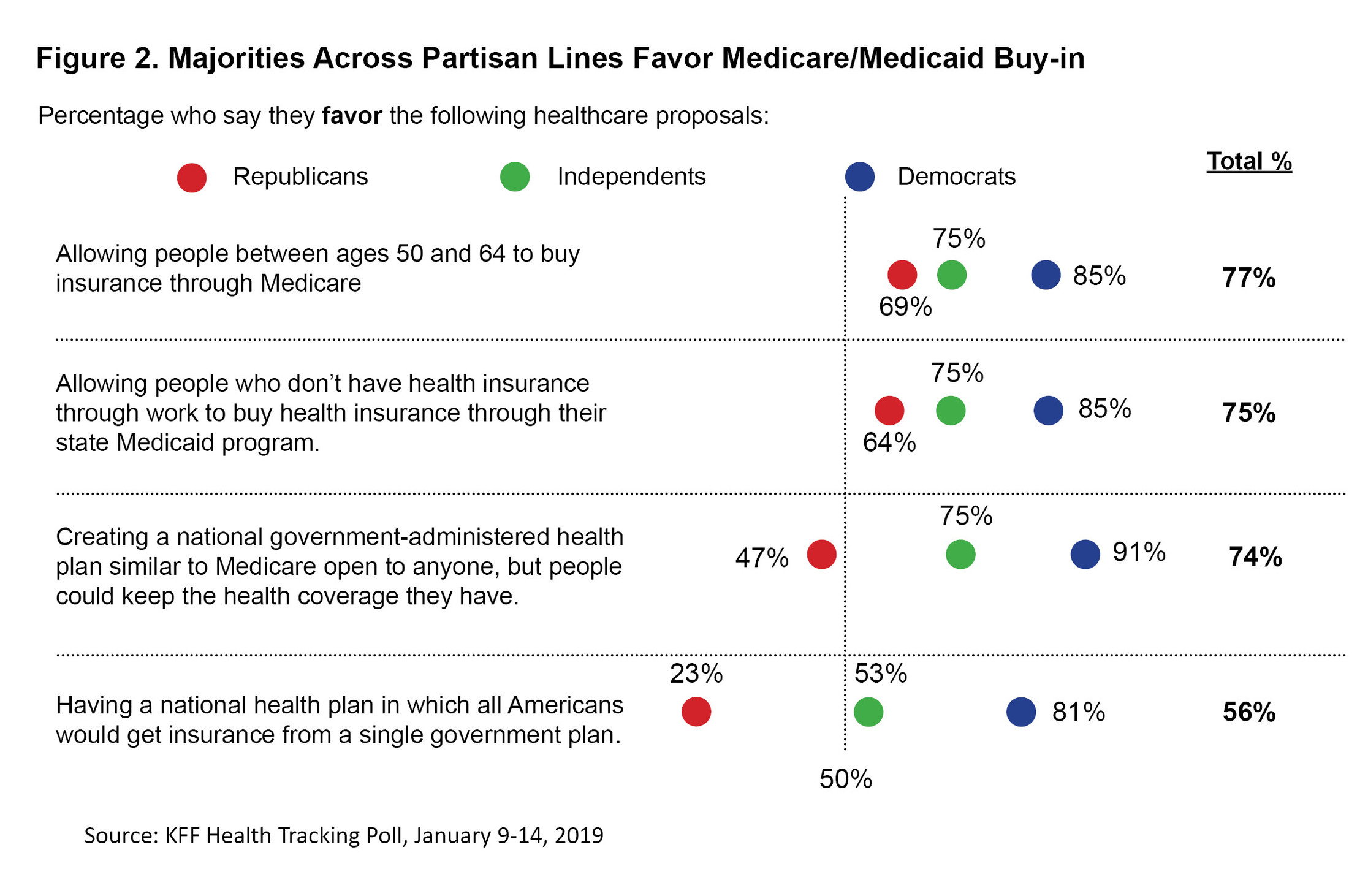

The Kaiser study also looks at a few other alternatives to going all-in on Medicare for All, and what people of different political stripes feel about those alternatives (Kirzinger, Muñana, & Brodie, 2019). These are:

- allowing people between the ages of 50 and 64 to buy insurance through Medicare

- allowing people who do not get health insurance from their employers to buy health insurance through a state Medicaid program instead of purchasing a private plan

- creating a national government-administered health plan similar to Medicare that is open to anyone, but allows people to keep their current coverage

- having a Medicare for All national health plan

Figure 2 below graphically displays their level of favorable responses to these options. It is interesting to note that in the Kaiser study, 55 percent of respondents believed they would be able to keep their current insurance plans under the program. This would only happen during the transition periods in the PFNHP and Senate plans.

Can Single Payer be Consumer-Centric?

Looking back at our first three articles and considering what consumers like and do not like about our current system, Medicare for All does check some useful boxes for consumers.

First, in a single-payer environment, there are no surprise bills, unless you count the sticker shock you might have every year by April 15 when you file your taxes.

The 11 million Americans who are currently without health insurance would be covered, everyone would have comprehensive health insurance coverage, and most would not have deductibles or direct charges for care. With everyone having access to preventive care, the result should be a healthier population.

Employers may be more satisfied and positive effects could trickle down to their employees. Currently, under the Affordable Care Act, employers with more than 50 employees must provide health insurance for them. Under a national single-payer system, employers would be freed from the financial and administrative burdens of providing health insurance coverage for their employees. Some posit that consumers might benefit from this indirectly as employers may use some of those savings on health benefits to raise salaries or improve other benefits.

Hospitals and clinicians would no longer suffer the administrative burdens of billing-related documentation. This will result in providers having more time to spend with patients, which was one of the big pluses in the model of direct primary care, presented in our previous article. However, some critics of the Senate single-payer plan say that complex payment procedures are still a part of that model, and this would take away from that vital attention to patients.

Full drug coverage with little or no co-payment or deductible incentivizes adherence to medication regimens, resulting in improved medical outcomes, which is what consumers are looking for.

People would not be able to keep their current insurance plans, and hundreds of thousands of workers (e.g., from the downsized health insurance business and hospital and clinician billing structures) would either need to be retrained for other work, or find new jobs. The brighter side of this is that the United States would likely significantly reduce its high per-capita healthcare spending. This is seen as both a pro and a con, depending on your vantage point. Much of the cost savings come from insurance company profits and overhead, reduced hospital and health system profits, administrative costs in provider organizations, and redundant bureaucracies in government programs after several systems from programs such as CHIP, Medicare and Medicaid are consolidated.

The reduction in the per-capita spending could go right back into the healthcare system to improve patient care and outcomes, and drive innovation in technology and cures—all high on the list for consumers striving for wellness.

Summary

The closest thing we have in this country to Medicare for all, of course, is Medicare. So how do people on Medicare rate their healthcare coverage and care?

In a November 2018 Gallup Poll on satisfaction with coverage and care, seniors and Medicaid/Medicare recipients rated their coverage and the healthcare care most positively among all group groups, with 9 in 10 seniors rating both positively.

For all adults covered by Medicare/Medicaid, 79 percent rated their healthcare coverage as excellent or good, compared to 70 percent for privately insured adults. On the other hand, 85 percent of adults covered by private insurance rated the healthcare they receive as excellent or good, compared to 79 percent for Medicare/Medicaid recipients. As might be expected, many more Medicare/Medicaid recipients are more satisfied with the costs they pay (70 percent vs. 51 percent) than those covered with private insurance (McCarthy, 2018).

It is interesting to note that the Gallup survey found that Americans are more satisfied with the personal costs they pay for health care than they are with the total national costs of healthcare. Since 2001, this survey has found that satisfaction with personal costs has ranged from 54 percent to 58 percent, while satisfaction with the total cost of healthcare in the United States has averaged 21 percent (20 percent in the latest survey). According to the study summary, “While Americans are more likely to be satisfied than dissatisfied with their own costs, they tend to see the overall U.S. healthcare system as overly expensive for others.”

The new year brought fresh debate over single-payer healthcare, as Democratic presidential challengers began hitting the campaign trail. It will be interesting to see whether the new bill in the House contains major departures from the Senate version, and whether that bill—and the individual platforms of the Democratic candidates—will move more toward some of those middle-of-the-road Medicare buy-in options mentioned earlier from the Kaiser study.

Still, single-payer healthcare does check many of the desired boxes for consumers, including cost and the improved care and attention they could potentially receive from providers. On the other hand, people generally seem to want to hold onto the plans they have, and those who might be enthusiastic at the prospect of coverage for everyone will have to weigh that against the tax bite.

In our next and last hypothetical consumer-oriented model, we take a 180-degree spin around to explore the private health insurance model.

References

Frankel, R. S. (2017, June 7). Worried sick about your health care? You’re not alone. Blog post. Bankrate. Retrieved from https://www.bankrate.com/banking/savings/money-pulse-0617/

Luhby, T., & Krieg, G. (2019, January 29). Harris backs ‘Medicare-for-all’ and eliminating private insurance as we know it. CNN. Retrieved from: https://www.cnn.com/2019/01/29/politics/harris-private-insurance-medicare/index.html

McCarthy, J. (2018, December 7). Most Americans still rate their healthcare quite positively. Gallup. Accessed at: https://news.gallup.com/poll/245195/americans-rate-healthcare-quite-positively.aspx

Pew Research. (2018). Pew Research Center September 2018 political survey: Final topline September 18-24, 2018. Retrieved from http://www.pewresearch.org/wp-content/uploads/2018/10/FT_18.10.03_HealthCare_Topline.pdf

Kirzinger, A., Muñana, C. & Brodie, M. (2019, January 23). Kirzinger, A., Muñana, C. & Brodie, M. (2019, January 23). KFF Health Tracking Poll–January 2019: The Public on next steps for the ACA and proposals to expand coverage. Kaiser Family Foundation. Retrieved at: https://www.kff.org/health-reform/poll-finding/kff-health-tracking-poll-january-2019